I’m an American living in Europe, so every summer, I hear a lot about air conditioning. Europeans love to tell me about how it’s good that Europe is largely not air conditioned; after all, air conditioning is just a high carbon luxury. Americans are just too used to their creature comforts, they say; if you’re serious about combating climate change, you have to stop relying on AC.

This is wrong. Increasingly, air conditioning isn’t a luxury. It is survival technology.

Life On A Warming Planet

The IPCC estimates that the earth has already warmed about one degree Celsius1 over the last century, and every year is hotter than the last.

We are already seeing the effects of this. It’s harder to concentrate in the heat, harder to be productive, harder to sleep, harder to think straight.

This manifests in a variety of domains:

For every degree the temperature rises, students learn less. Already, about 90,000 New York high school students had to take an extra year in school because they took exams in non-air-conditioned conditions and did worse than they otherwise would.

Workers are worse at their jobs too. At 95 degrees, worker productivity is just two-thirds of what it would be at 70 degrees. This already costs the US economy $100B a year, and is projected to rise to $500B a year by 2050.

Some of that may be because everyone’s tired - humans sleep worse in the heat, spending more time in shallow sleep and less time in deep, restful sleep.

Heat also makes people more irrational. Homicides and suicides go up on hot days - some 7% of US homicides may be caused by the heat.

And people die. Often, these deaths go unnoticed, because they don’t seem to be directly caused by the heat. Nonetheless, they are; heat increases the stress on the heart and makes other causes of death (like strokes and heart attacks) more common.

In 2003, Europe - where just 19% of the population has air conditioning - had an extended heat wave. 70,000 people died. This is not a small number - it’s comparable to the number of deaths in the worst weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2010, 54,000 Russians perished during another heat wave - almost as many as have died in the war in Ukraine.

Another 60,000 Europeans died to excess heat in 2022, even as Europeans remain reluctant to install AC for climate reasons.2

Heat Waves in the Developing World

Elsewhere in the world, air conditioning is even rarer. Consider India - where just 8% of households have air conditioning. That’s concerning, considering India’s dangerous combination of heat and humidity.

The human body relies on evaporative cooling via sweating - but that requires that our sweat be able to evaporate. That process is dependent on both the ambient temperature and the humidity. The most common measure of the combination of the two is called the wet bulb temperature, which effectively measures how cool your skin can become through sweating alone.

Europe’s 2003 heatwave reached wet bulb temperatures of around 26 degrees Celsius. The 2010 Russian heatwave reached wet bulb temperatures of about 28 degrees Celsius. At a wet bulb temperature of 32 degrees Celsius, even people who are “used to the heat” stop being able to carry out normal outdoor activities. A wet bulb temperature of 35 degrees Celsius is considered unsurvivable for more than a few hours.

To date, wet bulb temperatures like that are relatively rare. There have been a few hours in the United Arab Emirates that have been that hot, a few more hours in Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. So far, we have been lucky; we will not stay that way for long.

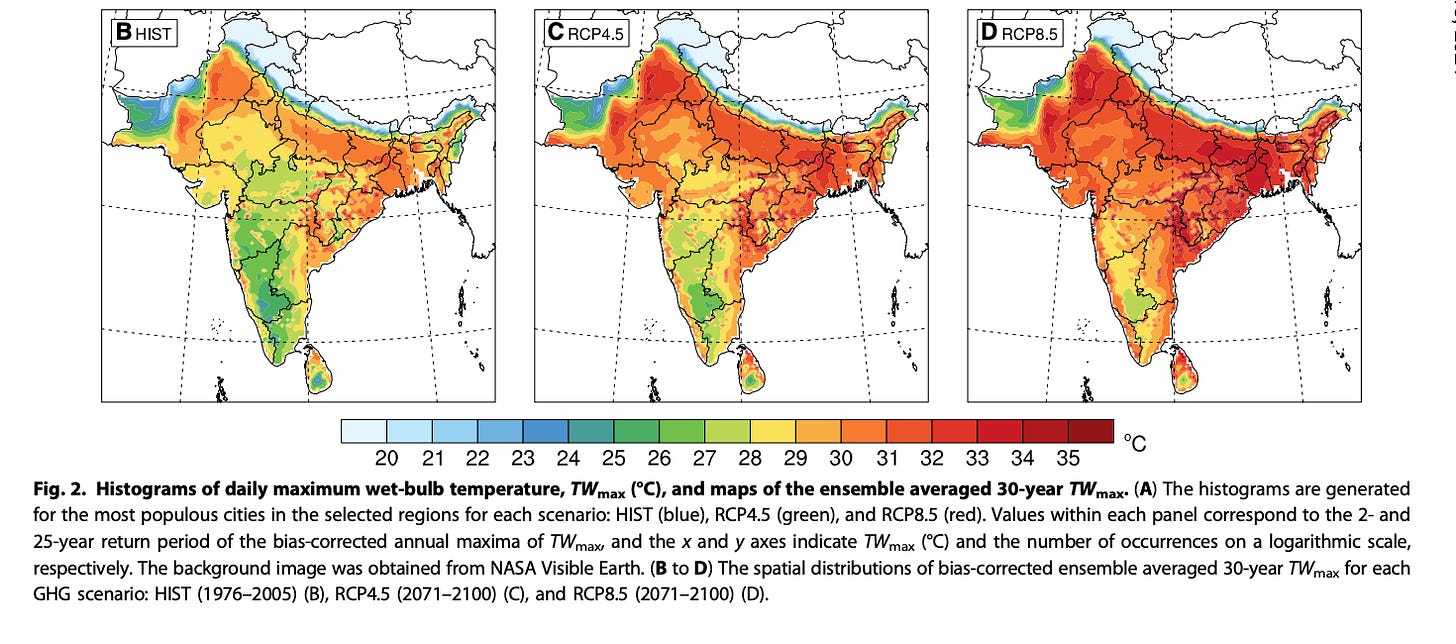

MIT professor Elfatih Eltahir has modeled the maximum wet bulb temperatures across densely populated regions of Asia under different climate scenarios:

(Figure shows projected maximum wet bulb temperatures in India over the next 30 years)

Over the last thirty years (the leftmost panel), maximum wet bulb temperatures edged into the low 30s. India is certainly hot and humid, but heat deaths are uncommon; it’s not fun to be outside some of the year, but it’s not actively dangerous.

The middle panel projects maximum wet bulb temperatures under a “moderate” emissions scenario, with about 2.25 degrees of warming. This is a reasonably likely scenario, a reasonable approximation of what the world will look like in 30 years.

Even under this model, parts of India will be on the cusp of uninhabitable. Every year would contain temperatures as high as the very hottest heatwaves today - and 45% of Indians still work outdoors, in agriculture. 55% of the population of this region will be expected to experience conditions that almost no humans have ever seen, under which outdoor work is completely impossible. Indeed, if one tried to work outside in those conditions, your organs would essentially cook - multi-organ failure is likely.

Even on cooler days, life would look very different than it does today. Remember that the US is already seeing increased crime, lower learning levels, and lower productivity - and 90% of American households have air conditioning.

In an environment where few people have air conditioning, the consequences would be much more severe. Current research suggests productivity in India can drop as much as 4% per degree of warming - suggesting that under two degrees of warming, the whole economy would contract by 8%. Under current heat projections, climate change alone could cause an economic depression. There aren’t good projections of how many deaths would result from this level of heat, but it could easily be hundreds of thousands per year.3

And that’s not even the worst case scenario. The rightmost panel shows wet bulb temperatures under RCP 8.5. This model is becoming less likely as more climate policies are adopted, but it’s still possible.

According to Eltahir’s model, large swathes of south Asia would become basically uninhabitable. 75% of the population of South Asia will experience wet bulb temperatures that could be fatal to healthly adults at least once a year; 30% of South Asia will experience high temperatures above those of Europe’s 2003 heat wave most of the year. The cities of Lucknow in Uttar Pradesh and Patna in Bihar (current populations 2.9 million and 2.2 million, respectively) would have annual high temperatures that exceed human survivability.

What Do We Do About This?

There are two billion people in South Asia. Do we abandon all of the Deccan Plateau and hope we can relocate everyone somewhere cooler? That seems difficult; even evacuating all of Lucknow and Patna seems unlikely.

Cue the humble air conditioner.

Heat waves do not have to be deadly; in the United States, the widespread use of air conditioning has decoupled the temperature-mortality relationship. AC units already save more than 200,000 lives a year.

In countries where AC use is widespread, productivity can remain high even as the climate warms. Indeed, Singapore’s founding prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, credited air conditioning for Singapore’s high productivity. For Yew, trying to run the government of a hot, humid country like Singapore, “air conditioning was a most important invention for us, perhaps one of the signal inventions of history.” (Singapore, incidentally, has much lower rates of heat-related mortality than surrounding countries.)

Certainly, there will be challenges to making AC more common. The French aren’t wrong; there could be climate consequences to scaling up AC usage. Air conditioning causes about 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions already; it is anticipated that by 2050, air conditioning could emit as much carbon as all of road transport does now if grids are not decarbonized.

Even if countries use greener sources for energy, many electricity grids aren’t even robust enough for the anticipated added burden. An AC unit doesn’t do much good in a blackout.

And, of course, ACs cost money; they can be unaffordable for some of the people who need them most.4 These are real challenges that will require substantial effort and investment to solve.

But solve them we must. We must ignore the scolding editorials about how we just need to get used to the heat and give up our air conditioning; millions of lives depend on it.

Approximately two Freedom Degrees.

49% of French people who don’t have AC say that they don’t want to use AC because AC use contributes to climate change.

For a very rough calculation: nearly all Indians would experience maximum wet bulb temperatures of >26 degrees every year (see figure 3, panel D). In Europe, a maximum wet bulb temperature of 26 degrees resulted in 60,000 deaths; India has 2.5x the population of Europe. India does have a younger population than Europe, but health care access is worse, more people work outdoors, and fewer people have AC. Thus, I think it is likely that the number of excess deaths would be >100,000.

Heat pumps are a much better solution in terms of emissions, but have a much higher upfront cost. This makes them difficult for many people in developing countries to afford.

I just got back to the US from Europe, and I feel you!

Have you read Ministry of the Future, by Kim Stanley Robinson? His first chapter vividly describes the suffering of people in Uttar Pradesh on a hot, wet day when there is a blackout and AC isn't available. It's frightening and meant to make real the need to stop climate change. But my immediate reaction was: Why in the world would we let it get this bad, even if temperatures rise--why not build more, reliable power and ensure AC is available? It is truly a life-saving technology, if combined with a reliable electrical grid, of course.