Where do the world’s poorest people live?

Are the poorest people in the world scratching out a living farming in rural India, or working long hours in a factory in China? Are they living in slums in Jakarta or Delhi?

Increasingly, the world’s poorest people are not in any of these places. That is not to say that there is not poverty there; about half of the world’s poorest people still live in stable-but-growing states. But as time goes on, the world’s poorest - those who live below the World Bank’s extreme poverty line of $2.15 a day - are increasingly concentrated not in stable countries, but in unstable ones.

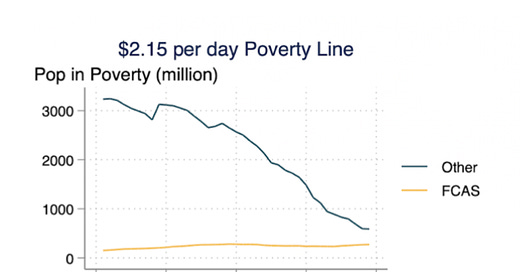

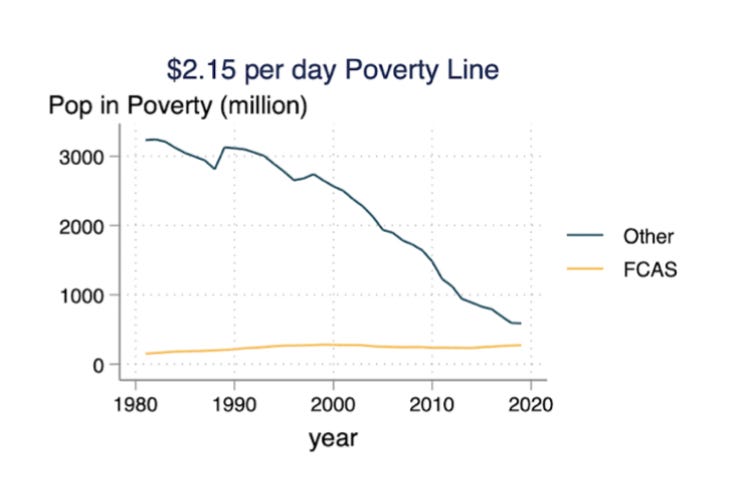

The below chart shows that while the number of people in poverty in stable states - labeled as “other” - has declined sharply, the number of people in poverty in fragile states - labeled as “FCAS (fragile and conflict-affected)” states - hasn’t:

(from CGD)

Right now, there are still more people in extreme poverty in stable states than in fragile ones, but this will soon change.

There is a pretty clear reason for this. Life is getting better in most poor countries. Progress is slow, and there is still a long way to go, but most people in low income countries will have a better life than their parents did, and their children will have a better life than they did. In India and China and Indonesia and Kenya and Tanzania, the number of people living in extreme poverty is decreasing over time.

This is not true in fragile states. Fragile states are states with weak state capacity, where the government is not perceived as legitimate, or where there is ongoing civil conflict. This includes places like Yemen, Afghanistan, and Somalia - but also Nigeria, Lebanon and Venezuela. In some of these places, the state is virtually nonexistent; in others, there is still some state providing public goods, but not a lot.

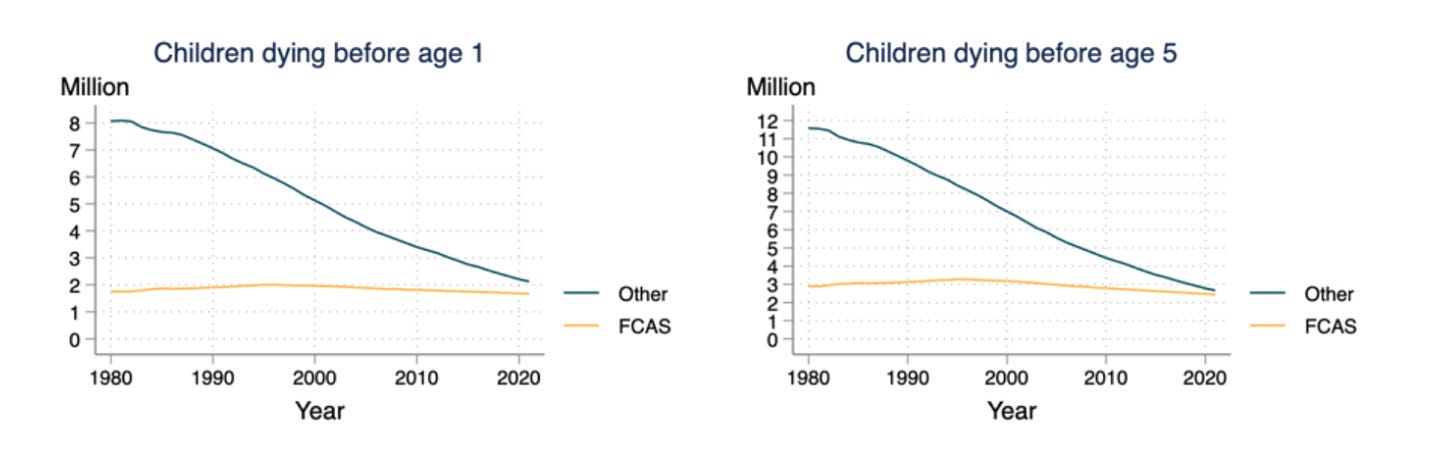

It is perhaps not a surprise that these countries have not seen the growth that more stable states have seen. It is easier to set up a business in Kenya than in Somalia; easier to work in EU-member Croatia than still-fragile Kosovo. But what is particularly striking is how much of a difference there is between fragile and stable states. Across a variety of indicators, things are getting better in stable states; there is not much evidence that things are getting better in fragile states. For instance, child mortality shows the same pattern:

(from CGD; again, FCAS = fragile and conflict-affected states; other = stable states)

This means that anyone interested in reducing extreme poverty must work on and in fragile states. The problem is that nothing really works in fragile states.

That’s basically the definition of a fragile state - the government is unable to provide services, and the population is skeptical of the government’s legitimacy (and their need to pay taxes). Contracts are suggestions, and in some fragile states, may be renegotiated at gunpoint.

It is famously difficult to operate in fragile and weak states. Let’s say, for instance, you run an NGO trying to distribute bednets. You need to procure some bednets, and get them to the people who need them. In a stable but poor state, this isn’t easy - the road quality in rural Uganda isn’t great, and driving can be a bit of an adventure - but it is possible.

In the DRC? Well, your first duty as an employer is to make sure that none of your employees get killed. What if they’re held up by bandits? Should your team carry cash, to pay off corrupt cops at roadblocks, or should they not, so they’re not a target for robberies? What if there’s a medical emergency? Where is the nearest hospital, anyway? Do they have power? The one paved road that you were planning to take was washed out in a flash flood; what’s the chance that your alternate route will be passable? It’s all the normal difficulties of operating in a poor country, plus several thousand more.

And this doesn’t just hold for NGOs. Generally, countries get out of poverty slowly, as more people move from the informal sector to the formal sector and incomes rise. It’s a very slow process, but over time: more people stay healthy for longer; more people go to school, more people get jobs in services or manufacturing instead of agriculture.

All of that progress can be undone very quickly. Fundamentally, you need peace and security for growth.

It’s not safe for your child to get to school because there’s a rebel group operating the area? Well, clearly they’re not going to go to school; their life matters more than attending school. The community health worker can’t make it to your village because the non-functional government hasn’t paid their salary in six months? Guess your kid isn’t getting treatment for malaria. That company that was going to open up a store in your village ended up backing out because it’s just too risky without a legal system that works? Well, you can always continue to farm. Every one of the thousands of baby steps needed for economic development can be derailed by state fragility and conflict.

Displacement is also very disruptive. People - very reasonably - do not want to become the next casualty in a war, and about 30 people will flee their homes for every conflict death. As they flee, though, services - both medical and commercial - are disrupted.

The worst consequences are medical. The people fleeing may be the doctors and nurses and community health workers that are needed to keep the community healthy, and there is a distinct lack of continuity of care while fleeing across the country or across borders. Most of the deaths in civil conflict don’t occur on the battlefield; they are caused by disrupted medical care rather than shrapnel wounds.

The monetary cost of disruption is minor by comparison, but is still significant. Some of the people who flee will be business owners. Shopkeepers can’t take their stores with them, farmers cannot take their crops. Though figures vary, a conflict can reasonably be assumed to decrease GDP/capita growth 5% a year. Since low or middle income countries grow at about 4% per year (on average), this means that as long as there is conflict, there will be no growth.

And without growth, extreme poverty will not decline. Reducing conflict is not sufficient for structural transformation, but it seems to be necessary.

The Case for Peacekeeping

So… what do we do about this? Prevent civil conflict and strengthen weak states? Yeah, that sounds super easy; I’ll get right on that. But there is a solution that has been shown to work: UN peacekeeping.

No, really. UN peacekeepers are widely perceived to be ineffective, blue-helmeted buffoons that wander around war zones being vaguely useless. They are rarely allowed to actually fire their guns. They just stand around looking official. They’re more like hall monitors than soldiers.

But peacekeeping - no matter how useless individual peacekeepers seem - has been shown to work. The academic literature is very clear on this:

Walter 2002 finds that if a third party is willing to enforce a signed agreement, warring parties are much more likely to make a bargain (5% vs. 50%) and the settlement is much more likely to hold (0.4% vs. 20%). 20% is not an amazing probability for sustained peace, but it sure beats 0.5%.

Page Fortna’s work shows that use of peacekeepers in a conflict reduced the likelihood of further war by 75%.

Hegre et al 2019 finds that increased deployment of peacekeepers could have reduced conflict by two-thirds in 2001-2013.

Blair 2020 finds that if peace is achieved, peacekeeping helps rebuild the rule of law in states where there is little rule of law to be found.

It turns out hall monitors are a thing that you need in a conflict. Ceasefires largely happen when neither side believes they can win; ceasefires fail when one of the two sides believes that they now have the advantage and would win if they return to war.

Often, one side uses the peace of the ceasefire to quietly rebuild its fighting strength, retrain and re-arm. This is usually against the terms of the peace agreement, but as long as the other side doesn’t know about it, you can get away with it. Getting away with re-arming is much harder, though, when there are blue-helmeted hall monitors wandering around.

It is true that individual peacekeepers can do very little about violations of a ceasefire. But they can call their boss, who calls their boss, and eventually the news reaches the UN security council, and then the US president is on the phone with the rebel leader asking why they violated the terms of the truce. Peacekeepers provide law by bringing the mandate of the UN with them; they can truly be a neutral third party.

None of that means that peacekeeping is a panacea.

Even though peacekeeping helps, it isn’t a guarantee of peace. After all, the longest running UN peacekeeping mission is trying to keep the peace between Israel and Palestine; it would be difficult to say its 76 year history has been a resounding success. Peacekeeping in Sudan, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo? It’s not clear those countries are better off than they would have been without peacekeepers. Peacekeeping gives you a chance at a sustained peace, but that’s all it is - a chance.

UN peacekeepers are also not precisely who I would choose to have teaching the rule of law. The UN only pays countries $1500 per soldier per month, so peacekeepers are often from countries where rule of law is limited to begin with. Sexual abuse by peacekeepers has been widespread enough to require a Wikipedia article.

But even with all of those caveats: peacekeeping is still probably the best solution that we have for fragile states. There are a few interventions that seem promising at reducing interpersonal violence at small scale (cognitive behavioral therapy, alternative dispute resolution) but we have little evidence on how they would work when scaled to a whole country. Peacekeeping is one of the few things that we do have strong evidence on. Peacekeeping works to reduce the risk of recurrent civil war.

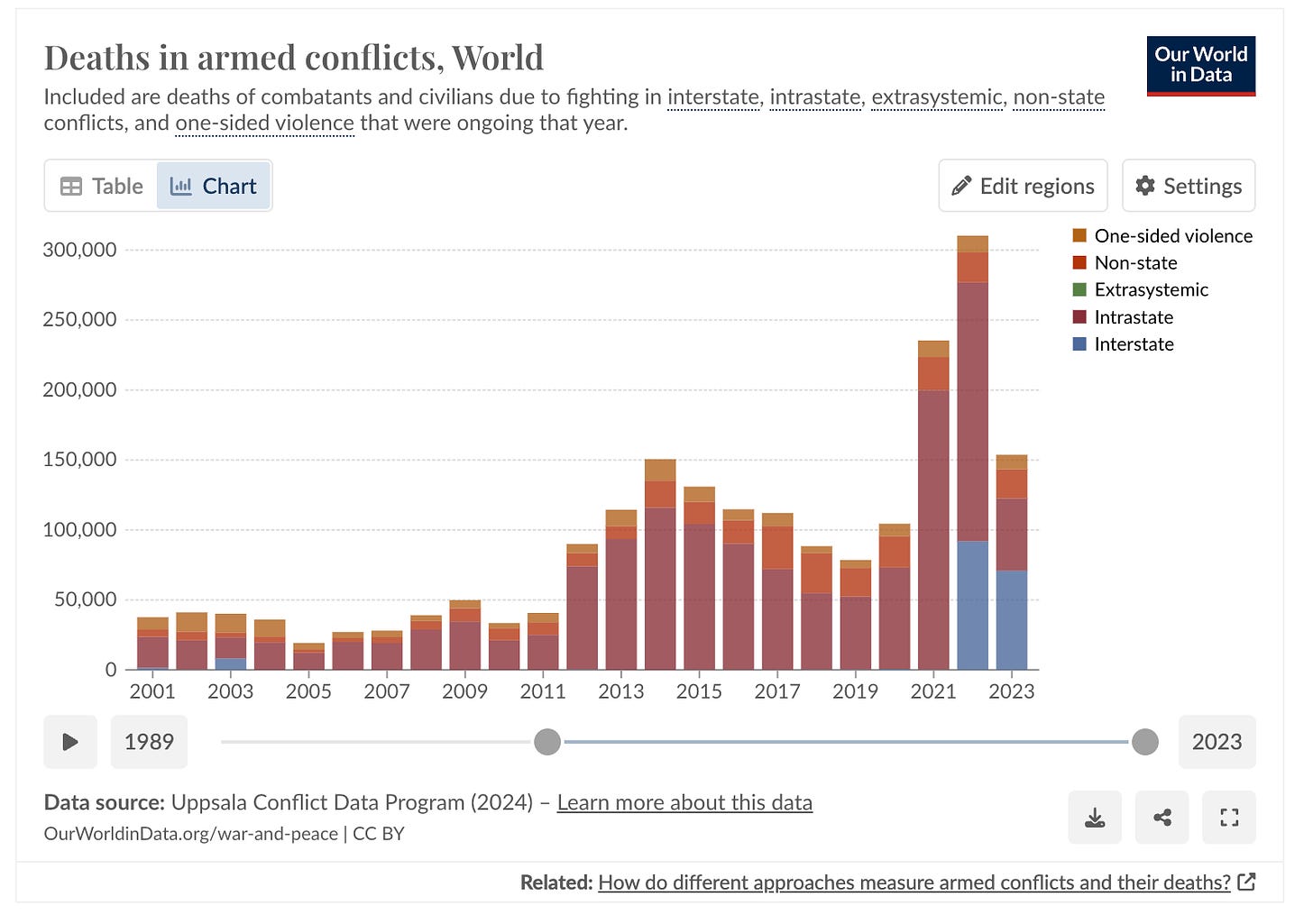

And yet we aren’t using it all that much. The UN Security Council seems to believe the endless articles about how useless peacekeepers are, and doesn’t seem all that enthusiastic about sending peacekeepers to new conflicts. Since 2010, the number of deployed peacekeepers has been largely flat, even as conflict deaths have increased:

(Chart from Our World in Data)

This is suboptimal. If the UN really is an organization dedicated to “maintaining international peace and security” and “promoting the well-being of peoples of the world”, peacekeeping is one of the best tools they have to support this mission. The UN may be bloated, bureaucratic and slow-moving, but this is something they do that definitely works.

But it is not just bleeding-heart humanitarians of the UN who should care about peace and peacekeeping. Anyone who cares about global poverty must also care about peace. Without stabilizing fragile states, all our progress at reducing global poverty will soon stall out, leaving hundreds of millions living on less than $2 a day.

Peace allows countries at least the prospect of growth. It is not a guarantee - growth is not always easy, even for countries at peace - but when there’s a civil war, it’s virtually impossible for a country to grow. For poverty to decrease, to health to improve, for life to get better, for countries to grow - there must be peace.

And if you care about peace, you should probably also care about peacekeeping.

Many thanks to Denise Melchin, Rob L'Heureux, Steve Newman, Kevin Kohler and Jeff Fong for comments and edits on this piece.

Food for thought. I am somewhat familiar with MONUSCO's work in Congo and UNWRA in Israel, both of which seem to be leaving. OTOH in Haiti peacekeeping does seem to be doing some good. I somewhat buy the general argument, but then I'm not sure what specific countries and conflicts I would be confident in adding peacekeepers to.